“Giving back hope” – six years of peacebuilding in Colombia. An interview with team leader and lawyer William Ramirez

I do this, because …

Interview with William Ramirez, lawyer and team leader for AMBERO Consulting Gesellschaft mbH in Colombia*

“Giving victims of violence some hope and showing that there can be mechanisms for change so that they can find new meaning in their lives and rebuild the social fabric […] motivates me,” says William Ramirez. The lawyer, who specialises in human rights and criminal proceedings, is the team leader for the ProPaz I and II projects implemented by AMBERO Consulting Gesellschaft mbH in Colombia. In this interview, he tells us how six years of peacebuilding and peace implementation have changed lives and why it is important for all team members to have a shared vision.

In Colombia, the BMZ (German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development) is supporting the political, social, and transitional justice process of dealing with the armed conflict that the country suffered for around 50 years. The ProPaz I and ProPaz II projects are integrated into this support plan and are being implemented under the leadership of GIZ. AMBERO is responsible for certain sub-modules of the projects on behalf of GIZ (German Development Agency). ProPaz I focussed on the transitional justice process and establishing historical truth, with a particular focus on institutional support. ProPaz II focussed on consolidating the peace process by pursuing a cross-institutional and psychosocial approach.

William, you are a Peruvian lawyer. Tell us how you came to work for AMBERO in Colombia?

Well, since I left university, I have worked on projects in the field of justice, especially in the areas of human rights and criminal proceedings. As fate would have it, I was in Guatemala as part of the development of the peace agreement**. There I supported the process of litigating cases of human rights violations and strengthening institutions of justice. I worked in Guatemala and Central America from 1995 to 2010.

One day, a German friend asked me if I would be interested in a project on the implementation of the new criminal procedure model in Peru, and I said yes. That was my first project with AMBERO, between 2010 and 2014.

What was the project about?

We supported the reform of the criminal proceedings and then also the transitional justice system. The project went very well, and when AMBERO approached me again in 2018 and asked me if I would like to work on an interesting project that supports and implements the peace agreement in Colombia on the topics of justice, memory and truth, I said: “Well, let’s give it a try.” And that’s how I joined the ProPaz I programme in August 2018.

Giving victims of violence some hope and showing that there can be mechanisms for change so that they can find new meaning in their lives and rebuild the social fabric. That motivates me.

And what motivated your continuous commitment to the implementation of human rights and peace agreements all these years?

Just recently we were talking to my daughter, who is already 16 years old and thinking about what she wants to do with her life, and the question came up as to why my wife, who is also a human rights expert, and I chose this branch.

Well, there are always different mechanisms to resolve conflicts and among them is the law, right? And within the law, there are human rights and the purpose of giving victims of violence some hope and showing that there can be mechanisms for change so that they can find new meaning in their lives and rebuild the social fabric. The pursuit for these solutions motivates me.

And indeed, the support for this peace agreement in Colombia is very interesting, partly because it brings in experience from all Latin American countries where peace agreements have already been implemented. So far, there have been good practices and experiences with reparations and truth commissions, but in Colombia these have been transformed into a normative transitional system. A normative structure with its own institutions and processes has been created here, which makes it possible to work towards reparation processes. That also motivated me.

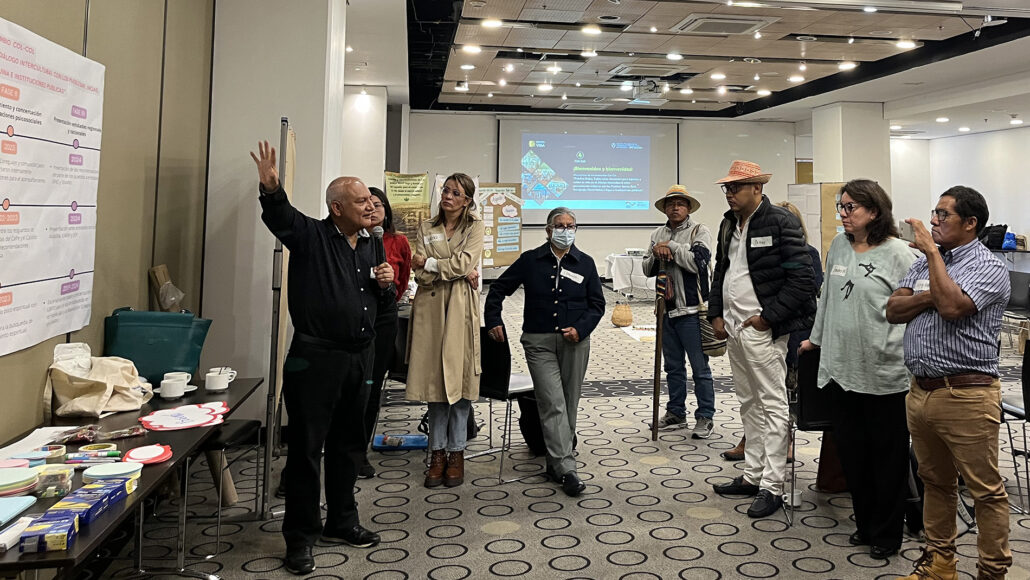

2024: William Ramirez during the “COL-COL” conference, an exchange of experiences among ethnic communities from the three project regions. (ProPaz II)

And what have you learned during your time as a team leader?

I have learnt a lot; I think it can be divided into two areas. On the one hand, there is the logic of the organisational culture and structure in the working teams, and on the other hand the thematic level, which concerns the relationship and the impact of the project products on the population.

As for the structure and organisation of a team: I am not Colombian and had never worked in Colombia before. So, I asked my team – one of the best I’ve ever worked with, both technically and personally – for an introduction: into the situation in Colombia, the problems, the culture, but also on how to deal with people. In return, I was able to show the team the general procedures for working with the GIZ guidelines. It was a process of getting to know each other, which helped us to understand each other better. Another thing that helped me a lot at the beginning was travelling with the teams into the interior of the country to get to know them better and find out how they relate to each other.

2018: The ProPaz I team with William Ramirez (fourth from left)

2024: The ProPaz II team with William Ramirez (fourth from left) and AMBERO project manager Ginela Salazar on a backstopping visit (far right)

2024: Good practices and exchange of experiences between three indigenous communities and the regional institutions in Caquetá (ProPaz II)

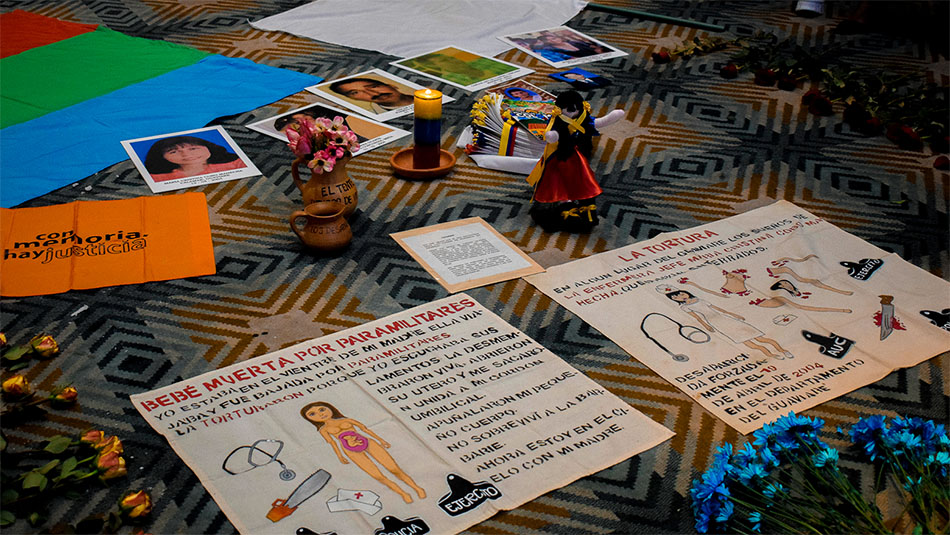

2022: Working group in Caquetá with women who have experienced violence in the context of the armed conflict. (ProPaz II)

2024: Exchange of experiences among ethnic communities from the three project regions “COL-COL” (ProPaz II)

* This interview was originally made for the internal Dorsch Online Platform where it was published in August 2024. This version has been adapted with permission of Dorsch Online for the publishing on the AMBERO website.

**Editor’s note: After 36 years of civil war in Guatemala, which cost around 200,000 lives, a peace agreement was signed between the guerrillas and the government in December 1996, officially ending the civil war.